Some ‘friendly’ bacteria backstab their algal pals. Now we know why

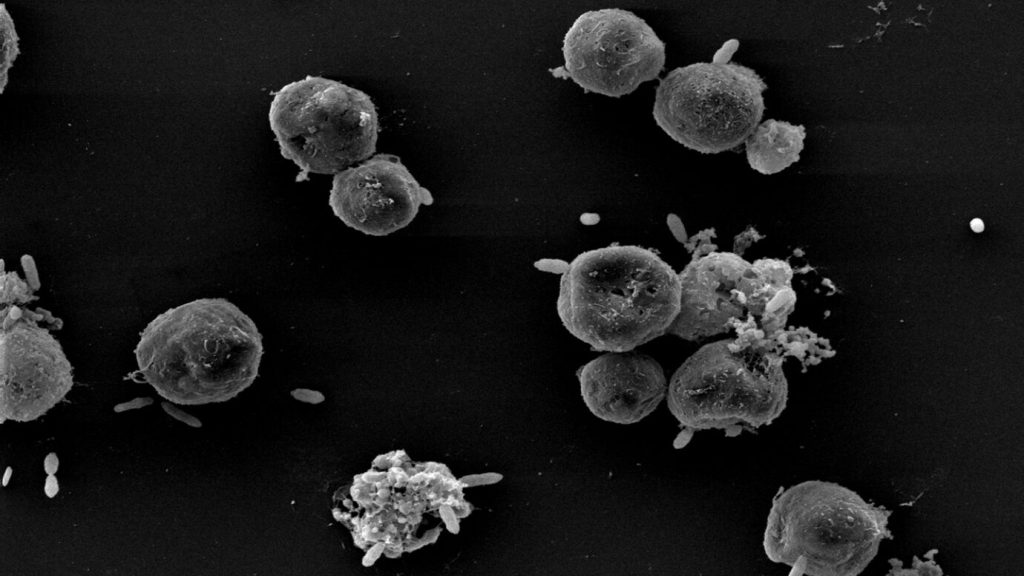

The photosynthesizing plankton Emiliania huxleyi has a dramatic relationship with its bacterial frenemies. These duplicitous bugs help E. huxleyi in exchange for nutrients until it becomes more convenient to murder and eat their hosts. Now, scientists have figured out how these treacherous bacteria decide to turn from friend to foe.

One species of these bacteria appears to keep tabs on health-related chemicals produced by E. huxleyi, researchers report January 24 in eLife. The bacteria maintain their friendly facade until their hosts age and weaken, striking as soon as the vulnerable algae can’t afford to keep bribing them with nutrients. The finding could help explain how massive algal blooms come to an end.

The bacteria is “first establishing what we call the ‘first handshake,’” says marine microbiologist Assaf Vardi of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel. “Then it will shift into a pathogen.”

E. huxleyi’s partnership with these bacteria, which belong to a group called Roseobacter, might be best described as a love-hate relationship. The single-celled alga can’t produce the B vitamins it needs on its own, so it offers up nutrients to lure in Roseobacter that can (SN: 7/8/16). The trade is win-win — at least until the bacteria decide they’d be better off slaying and devouring their algal hosts than sticking around in peaceful coexistence.

Sometimes called the “Jekyll-and-Hyde” trait, this kind of bacterial backstabbery shows up everywhere from animal guts to the open seas. But it wasn’t clear before how Roseobacter decide it’s the right moment to murder E. huxleyi.

Vardi’s team exposed a type of Roseobacter that lives with E. huxleyi to chemicals taken from algae that were either young and growing or old and stagnant. The team also introduced the bacteria to extra doses of a certain health-signaling algal chemical.Looking at which genes the bacteria activated in the different experiments revealed how and why they switched from friend to foe.

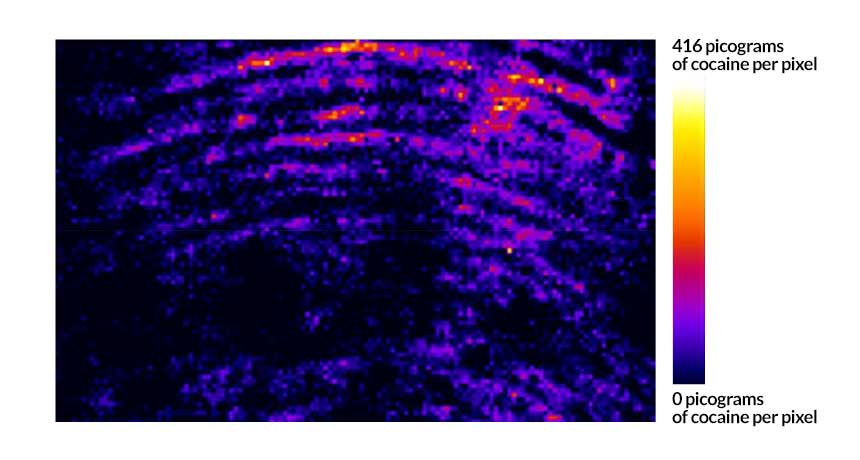

The bacteria kill their algal pals when exposed to high concentrations of a sulfur-containing chemical called DMSP, the researchers found. E. huxleyi leaks more and more DMSP as it ages. This eventually cues its duplicitous microbial partners to go rogue, kill their aging host, and kick their genes for nutrient-grabbing proteins and flagella — whiplike tails used to swim — into overdrive.

It’s an “eat-and-run strategy,” says Noa Barak-Gavish, a microbiologist at ETH Zurich. “You eat up whatever you can and then swim away to avoid competition … [and] to find alternative hosts.”

DMSP isn’t the only figure in this deadly chemical calculus. E. huxleyi can sate its companion’s bloodlust with a bribe of benzoate, a nutrient that Roseobacter can use but most bacteria can’t.

While it’s clearer now what drives the bacteria to kill their hosts, their murder weapon remains a mystery. Vardi says his group has some hunches to follow up on.

This kind of frenemies relationship could be a key factor in controlling the boom and bust of massive algal blooms if other phytoplankton and bacteria have a similar dynamic, says Mary Ann Moran of the University of Georgia in Athens, who was not involved in the study. Algal blooms can be toxic (SN: 8/28/18). But they also “fix” enormous amounts of carbon dioxide into biomass and are a major source of organic carbon to the ocean.

“Phytoplankton fix half of all the carbon on the planet, and probably 20 percent to 50 percent of what they fix … actually goes right to bacteria,” she says. So if this kind of relationship controls how carbon flows through the ocean, “that is something that we would really like to understand.”