The standard model of particle physics passed one of its strictest tests yet

No one has ever probed a particle more stringently than this.

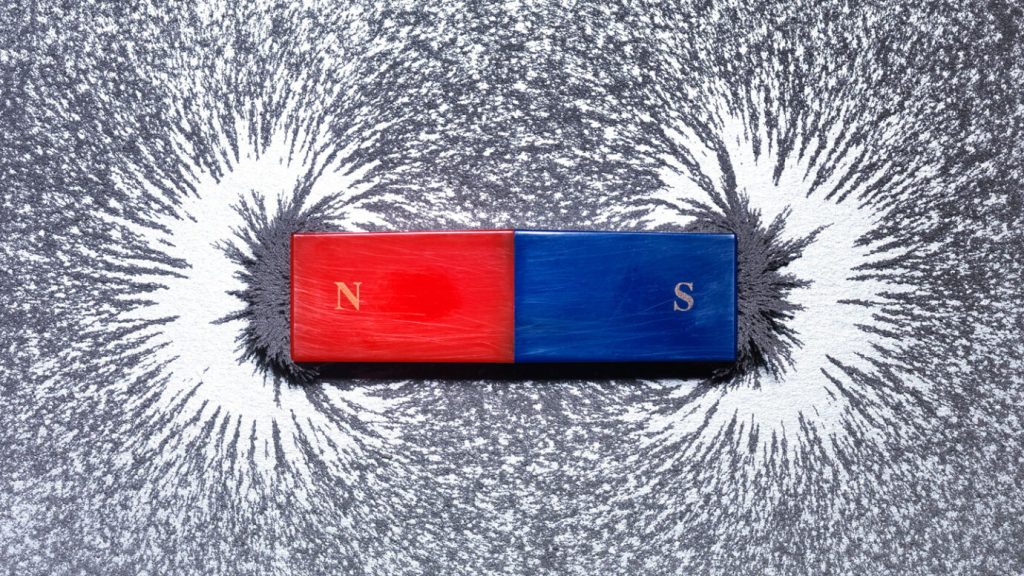

In a new experiment, scientists measured a magnetic property of the electron more carefully than ever before, making the most precise measurement of any property of an elementary particle, ever. Known as the electron magnetic moment, it’s a measure of the strength of the magnetic field carried by the particle.

That property is predicted by the standard model of particle physics, the theory that describes particles and forces on a subatomic level. In fact, it’s the most precise prediction made by that theory.

By comparing the new ultraprecise measurement and the prediction, scientists gave the theory one of its strictest tests yet. The new measurement agrees with the standard model’s prediction to about 1 part in a trillion, or 0.1 billionths of a percent, physicists report in the February 17 Physical Review Letters.

When a theory makes a prediction at high precision, it’s like a physicist’s Bat Signal, calling out for researchers to test it. “It’s irresistible to some of us,” says physicist Gerald Gabrielse of Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill.

To measure the magnetic moment, Gabrielse and colleagues studied a single electron for months on end, trapping it in a magnetic field and observing how it responded when tweaked with microwaves. The team determined the electron magnetic moment to 0.13 parts per trillion, or 0.000000000013 percent.

A measurement that exacting is a complicated task. “It’s so challenging that nobody except the Gabrielse team dares to do it,” says physicist Holger Müller of the University of California, Berkeley.

The new result is more than twice as precise as the previous measurement, which stood for over 14 years, and which was also made by Gabrielse’s team. Now the researchers have finally outdone themselves. “When I saw the [paper] I said, ‘Wow, they did it,’” says Stefano Laporta, a theoretical physicist affiliated with University of Padua in Italy, who works on calculating the electron magnetic moment according to the standard model.

The new test of the standard model would be even more impressive if it weren’t for a conundrum in another painstaking measurement. Two recent experiments, one led by physicist Saïda Guellati-Khélifa of Kastler Brossel Laboratory in Paris and the other by Müller, disagree on the value of a number called the fine-structure constant, which characterizes the strength of electromagnetic interactions (SN: 4/12/18). That number is an input to the standard model’s prediction of the electron magnetic moment. So the disagreement limits the new test’s precision. If that discrepancy were sorted out, the test would become 10 times as precise as it is now.

The stalwart standard model has stood up to a barrage of experimental tests for decades. But scientists don’t think it’s the be-all and end-all. That’s in part because it doesn’t explain observations such as the existence of dark matter, an invisible substance that exerts gravitational influence on the cosmos. And it doesn’t say why the universe contains more matter than antimatter (SN: 9/22/22). So physicists keep looking for cases where the standard model breaks down.

One of the most tantalizing hints of a failure of the standard model is the magnetic moment not of the electron, but of the muon, a heavy relative of the electron. In 2021, a measurement of this property hinted at a possible mismatch with standard model predictions (SN: 4/7/21).

“Some people believe that this discrepancy could be the signature of new physics beyond the standard model,” says Guellati-Khélifa, who wrote a commentary on the new electron magnetic moment paper in Physics magazine. If so, any new physics affecting the muon could also affect the electron. So future measurements of the electron magnetic moment might also deviate from the prediction, finally revealing the standard model’s flaws.