A new look at the ‘mineral kingdom’ may transform how we search for life

If every mineral tells a story, then geologists now have their equivalent of The Arabian Nights.

For the first time, scientists have cataloged every different way that every known mineral can form and put all of that information in one place. This collection of mineral origin stories hints that Earth could have harbored life earlier than previously thought, quantifies the importance of water as the most transformative ingredient in geology, and may change how researchers look for signs of life and water on other planets.

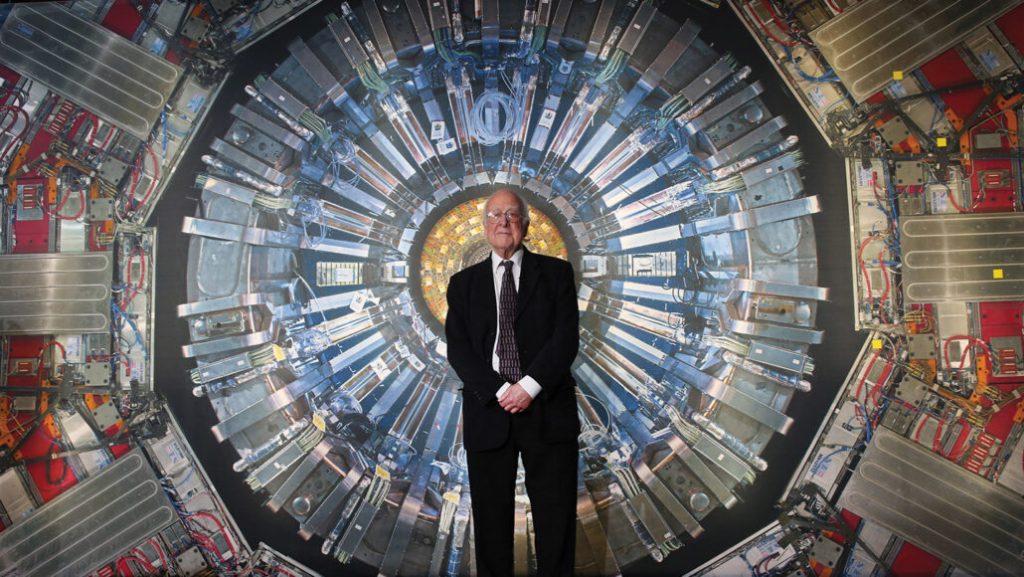

“This is just going to be an explosion,” says Robert Hazen, a mineralogist and astrobiologist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C. “You can ask a thousand questions now that we couldn’t have answered before.”

For over 100 years, scientists have defined minerals in terms of “what,” focusing on their structure and chemical makeup. But that can make for an incomplete picture. For example, though all diamonds are a kind of crystalline carbon, three different diamonds might tell three different stories, Hazen says. One could have formed 5 billion years ago in a distant star, another may have been born in a meteorite impact, and a third could have been baked deep below the Earth’s crust.

So Hazen and his colleagues set out to define a different approach to mineral classification. This new angle focuses on the “how” by thinking about minerals as things that evolve out of the history of life, Earth and the solar system, he and his team report July 1 in a pair of studies in American Mineralogist. The researchers defined 57 main ways that the “mineral kingdom” forms, with options ranging from condensation out of the space between stars to formation in the excrement of bats.

The information in the catalog isn’t new, but it was previously scattered throughout thousands of scientific papers. The “audacity” of their work, Hazen says, was to go through and compile it all together for the more than 5,600 known types of minerals. That makes the catalog a one-stop shop for those who want to use minerals to understand the past.

The compilation also allowed the team to take a step back and think about mineral evolution from a broader perspective. Patterns immediately popped out. One of the new studies shows that over half of all known mineral kinds form in ways that ought to have been possible on the newborn Earth. The implication: Of all the geologic environments that scientists have considered as potential crucibles for the beginning of life on Earth, most could have existed as early as 4.3 billion years ago (SN: 9/24/20). Life, therefore, may have formed almost as soon as Earth did, or at the very least, had more time to arise than scientists have thought. Rocks with traces of life date to only 3.4 billion years ago (SN: 7/26/21).

“That would be a very, very profound implication — that the potential for life is baked in at the very beginning of a planet,” says Zachary Adam, a paleobiologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison who was not involved in the new studies.

The exact timing of when conditions ripe for life arose is based on “iffy” models, though, says Frances Westall, a geobiologist at the Center for Molecular Biophysics in Orléans, France, who was also not part of Hazen’s team. She thinks that scientists need more data before they can be sure. But, she says, “the principle is fantastic.”

The new results also show how essential water has been to making most of the minerals on Earth. Roughly 80 percent of known mineral types need H2O to form, the team reports.

“Water is just incredibly important,” Hazen says, adding that the estimate is conservative. “It may be closer to 90 percent.”

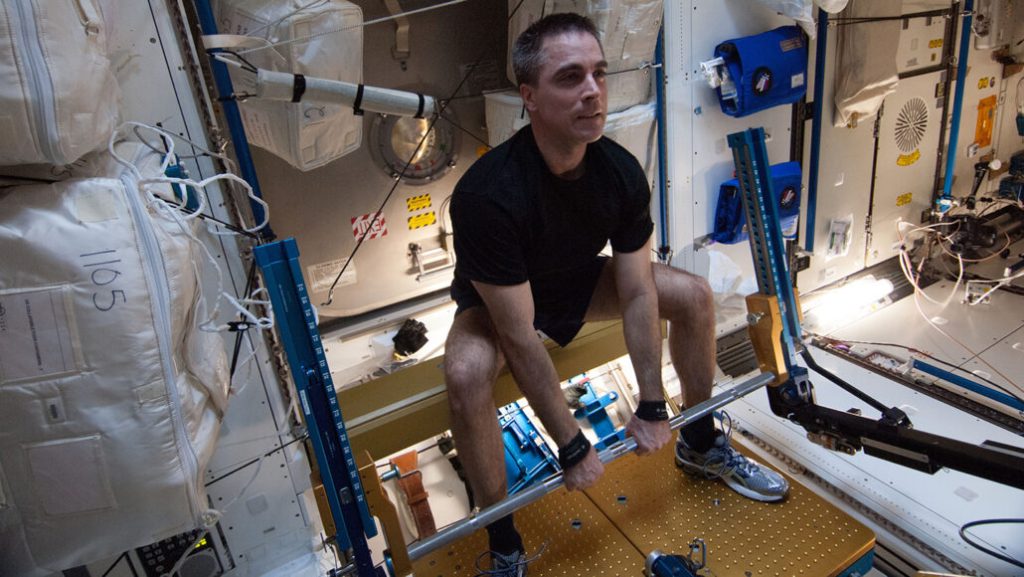

Taken one way, this means that if researchers see water on a planet like Mars, they can guess that it has a rich mineral ecosystem (SN: 3/16/21). But flipping this idea may be more useful: Scientists could identify what minerals are on the Red Planet and then use the new catalog to work backward and figure out what its environment was like in the past. A group of minerals, for example, might be explainable only if there had been water, or even life.

Right now, scientists do this sort of detective work on just a few minerals at a time (SN: 5/11/20). But if researchers want to make the most of the samples collected on other planets, something more comprehensive is needed, Adam says, like the new study’s framework.

And that’s just the beginning. “The value of this [catalog] is that it’s ongoing and potentially multigenerational,” Adam says. “We can go back to it again and again and again for different kinds of questions.”

“I think we have a lot more we can do,” agrees Shaunna Morrison, a mineralogist at the Carnegie Institution and coauthor of the new studies. “We’re just scratching the surface.”