Women in sports are often underrepresented in science

On April 19, 1966, Roberta Gibb became the first woman to (unofficially) finish the Boston marathon. Women were officially allowed to enter the race in 1971, and Boston medaled its first female winner in 1972 — the year that also saw the passage of Title IX — the amendment that prohibits discrimination based on sex in education programs or any program receiving federal funding. This year, 13,751 women crossed the Boston marathon finish line, making the finisher list 45 percent female. In the last 50 years, other sports have also welcomed in women, from weightlifting to rugby to wrestling. And of course, women exercise noncompetitively, lifting weights, holding yoga poses and putting in hours on the track and in the gym.

Women are making up for a historical bias against them in sports. Not surprisingly, there’s also historically been a bias in sports science. “If you went all the way back to the 1950s, a lot of exercise physiology studies about metabolism talk about the 150-pound-man,” says Bruce Gladden, an exercise physiologist at Auburn University in Alabama and the editor in chief of the journal Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. “That was the average medical student.” It was a matter of convenience, studying the people nearest at hand, he explains.

Over time, athletes (and convenient student populations) have become more diverse, but diversity in studies of those athletes has continued to lag behind. When Joe Costello, an exercise physiologist at the University of Portsmouth in England, began studying the effects of extreme cold exposure on training recovery in athletes, he found that women were under-represented in the field compared to men. He wondered, he says, “is that the case across the board in sports science?”

Digging through three influential journals in the field — Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, the British Journal of Sports Medicine and the American Journal of Sports Medicine — Costello and his colleagues analyzed 1,382 articles published from 2011 to 2013, which added up to more than six million participants. The percentage of female participants per article was around 36 percent, and women represented 39 percent of the total participants, the scientists reported in April 2014 in the European Journal of Sport Science.

“In my opinion, it’s not enough,” he says. The numbers are relatively close to the gender breakdowns in competitive sport, he notes, but participation in noncompetitive exercise and casual running is a lot closer to a 50:50 breakdown, and the studies don’t reflect that.

Despite the gap, Costello’s study did show that women are represented in exercise science studies in general. But I wondered if the trend was improving — and if the type of study mattered. Are scientists studying women in, say, studies of metabolism, but neglecting them in studies of injury? I looked at published studies in two top exercise physiology journals and found that women remain under-studied, especially when it comes to studies of performance. Reasons for this under-representation abound, from menstrual cycles to funding to simple logistics. But with recent requirements for gender parity from funding agencies, reasons are no longer excuses. When it comes to the race to fitness, women are well out of the starting blocks, but the science still has some catching up to do.

Let’s look at the data

I followed Costello’s lead and looked at studies published in Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise and the American Journal of Sports Medicine, this time looking at the first five months of 2015(the former journals had articles available for free through May 2015; the latter granted me access. The third journal in the previous study, the British Journal of Sports Medicine, would only grant me access on a case-by-case basis). I excluded single case studies, animal studies, cell studies, studies involving cadavers and studies that dealt with coaches’ or doctors’ evaluations. I also excluded studies where the gender breakdown of participants wasn’t given (11 studies that included people didn’t mention the gender of the participants), and studies where there would be no reason to include women (such as those involving prostate cancer recovery).

That left me with 188 studies that included 254,813 participants. Of the 188 studies, 138, or 73 percent involved at least some women. But overall, women made up only 42 percent of participants. While 27 percent of the studies included only men, only 4 percent were studies of only women.

These results were similar to those Costello and his group showed in 2014. But I also wondered what, exactly, those women were being studied for. I took the 188 studies and divided them into six categories:

Studies on metabolism, obesity, sedentary behavior, weight loss and diabetes

Studies of nonmetabolic diseases

Basic physiology studies

Social studies, including uses of pedometers and group exercise

Sports injury

Performance studies.

In studies of metabolism, obesity, weight loss and diabetes (23 total studies), women were included in 87 percent of studies and represented 45 percent of participants, getting relatively close to gender parity. For nonmetabolic diseases (18 studies), 85 percent of studies included women, and they represented 44 percent of participants.

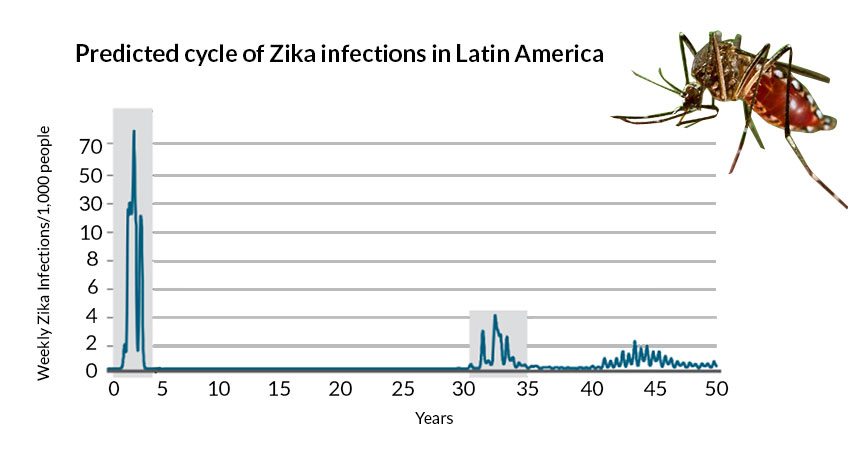

Out of 188 studies, the number of studies involving women ranged from 36 percent in performance to 100 percent in social studies.

In basic physiology studies (11 total studies), including studies of knee and muscle function and studies of people in microgravity, women were included in 45 percent of studies, and represented 42 percent of all participants.

Women were represented in 100 percent of social studies (seven papers) and made up 60 percent of the participants. These included studies such as self-cognition, how well people adhere to wearing activity trackers, and the influence of meet-up groups on exercise. “Women are more likely to take part in [or] be recruited to group training programs than men,” notes Charlotte Jelleyman, an exercise physiologist at the University of Leicester in England.

The most striking differences came when studying performance and sports injury. There were 102 studies of sports injury and recovery, from concussions and elbow and shoulder repair in baseball players to studies of injury in surfers. Women were present in 80 percent of these studies, but made up 40 percent of participants.

I was especially interested in the large number of studies (38 total) on knee and ACL repair. In these studies, women were present in 94 percent of studies, but were only about 42 percent of participants. “That’s a case where you would think there would be more emphasis,” Gladden notes. “ACL injuries are much more prevalent in female athletes.”

Out of more than 250,000 participants in the 188 studies analyzed, the majority were men, particularly in analyses of sports performance and injury.

But the biggest difference came in sports performance — training to get better, recover faster and perform stronger. Of 30 studies, 39 percent involved women, and women made up almost 40 percent of participants. But this result was heavily skewed by a single study of more than 90,000 participants, which examined sex differences in pacing during marathons. When this study was removed, the total number of participants in all performance studies dropped to 4,001. And the percentage of female participants dropped with it — to 3 percent. Scientists may be trying to get at the secrets of the best athletes, but to do so, they are mostly looking in men.

Time, money and menstrual cycles

There are many reasons why women might be under-represented in exercise science. One is the same reason that haunts many sex disparities in biological research — the menstrual cycle.

With monthly hormone cycles, “[we] have to test [women] at certain phases,” even if you’re studying something seemingly unrelated, such as knee pain, explained Mark Tarnopololsky, a neurometabolic specialist at McMaster University, who has extensively studied sex differences in exercise. “One has to choose which phase — follicular or luteal phase — so I think when physiologists are limited in their funds, it’s easier to get guys to come in at any time.”

For some types of studies, scientists note that no previous studies have found sex differences. So scientists just study men — with no menstrual cycle to worry about — and apply the results to women. But “it’s not good enough,” says Jelleyman. “Just to say that because it works in men and previous studies have found no sex differences we assume it will work on women too – you have to show it.”

Many scientists worry that cycling hormones means variable data points, so it’s easier to study men and state that the results probably apply to women, too. But that’s a cop out, says Marie Murphy, an exercise scientist at Ulster University in Northern Ireland. “If you revisit [women] in the same phase, they should be no more variable than a man,” she notes. “You return to them 28 days later and that’s easy enough. It’s not a difficult thing to do. But I think if you’re looking for an excuse you’ll find one.”

Using that excuse can mean missing important differences. Before Gibb’s Boston run in 1966, many people — including scientists — viewed distance running and extreme exercise as somehow unhealthy for women, Tarnopololsky explains. After his lab studied differences in metabolism in men and women during endurance exercise, his group found that “Women were at least as good, if not better able to withstand the rigors of the exercise.”

But menstrual cycles aside, studies are expensive, particularly studies involving people. In many cases, simplifying the study population is the only way to complete the work on time and within budget. As a member of the coaching teams associated with elite athletes, Louise Burke, a sports nutritionist at the Australian Institute of Sport, says she takes her research chances where she can find them. For a recent study of male race walkers, “when we decided to do the study I did think we’d have female race walkers,” she says. But she found that the pool of potential female participants was small. “We didn’t have a lot in Canberra,” she recalls. “Of that ones that were of the right caliber, we had people being injured, a couple who were doing a race that wouldn’t make them available.”

And when logistics shoot down one sex in a study, it will be the women who lose out. “Conference organizers are careful and include symposia on sex differences,” says John Hawley, an exercise physiologist at Australian Catholic University. But when it comes to actually doing studies, there can be challenges. Many of Hawley’s studies are invasive, involving biopsies that leave scars. And many women aren’t willing to get scarred for science. “If I go out to a triathlon and say to the females, ‘we’d like to do invasive work,’ they’re like ‘ooh, no biopsies,’” Hawley says. “It’s a legitimate practical issue.”

Finally, there are also cultural reasons that women end up underrepresented. Female athletes don’t get the same TV time as male athletes, and the players don’t get paid as much, even though, as in soccer, the women’s national team is more highly ranked than the men’s. This disparity might also result in [gender] disparity in performance studies, Gladden suggests. “Science unfortunately isn’t immune to those same problems.”

Leveling the playing field

Calls for equality in exercise research continue. In a recent article in The Sport and Exercise Scientist, Murphy looked at the March issue of the Journal of Sports Sciences, and found that the 13 papers in the issue included 852 participants, but only 103 women, a dismal participation rate of only 12 percent.

While Murphy notes that other fields of study may have similar findings, exercise science needs to do better. “It’s quite simple,” she says. “If we want to apply the findings to men and women, we need to test our hypotheses and do our measures in research involving men and women.”

The lack of parity for female research participants “should be alarming,” Hawley says. He notes that while scientists bear some responsibility, “the funding bodies and editors of journals should be asking more serious questions.” Scientists who peer-review each other’s work should also ask hard questions, he says. “Peer review is failing as well….The typical responses [are] ‘unfortunately the budget does not permit females’ (a complete white lie of course), and time and practicalities. It’s not an excuse.”

As is true in many areas of science, as more women join the ranks of scientists studying exercise, they are more likely to include women in their studies. But Murphy notes that it won’t solve the problem. “I don’t think scientists think of it unless they have a particular interest in the area,” she says. “There are really good women researchers [in exercise science], but they study men, and the men study men! We’re not doing ourselves any favors.”

The broader impact of this gender imbalance is that training, fitness and diet recommendations for performance and recovery are based on science that may have only been done in men, and then downsized to fit women. Sometimes it may make no difference. But what if it could? In the end, the road to stronger, better, faster and healthier is one with studies that include everyone. “It is important to show that the general principles of exercise effectiveness are applicable to all populations whether it be males or females, older or younger, ethnically different or diseased populations,” says Jelleyman. “Sometimes it emerges that there are differences, other times less so. But it is still important to know this so that recommendations can be based on relevant evidence.”