Camera trap catches a badger burying a cow

The American badger is known to cache carrion in the ground. The animals squirrel away future meals underground, which acts something like a natural refrigerator, keeping their food cool and hidden from anything that might want to steal it. Researchers, though, had never spotted badgers burying anything bigger than a jackrabbit — until 2016, when a young, dead cow went missing in a study of scavengers in northwestern Utah.

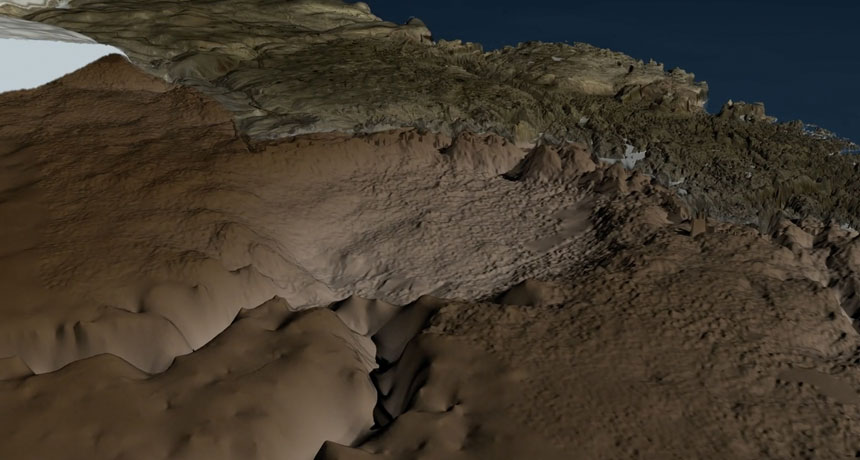

That January, University of Utah researchers had set out seven calves (all of which had died from natural causes) weighing 18 to 27 kilograms in the Great Basin Desert, each monitored by a camera trap. After a week, one of the carcasses went missing, even though it, like the others, had been staked in place so nothing could drag it off. But perhaps a coyote or mountain lion managed the feat, the researchers thought.

Then they checked the camera. What they found surprised them.

The images showed a badger happening upon the calf on January 16. The next evening, the badger returned and spent four hours digging below and around the bovine, breaking for only five minutes to snack on its find. It came back and continued digging the next afternoon and the following morning, by which time the calf had fallen into the crater the badger had dug. But that wasn’t the end. The badger then spent a couple more days backfilling the hole, covering its find and leaving itself a small entrance.

The badger stayed with his meal for the next couple of weeks, venturing out briefly from time to time. (It’s impossible to know where the badger went, but getting a drink is one possibility, says the study’s lead author Ethan Frehner.) By late February, the badger was still visiting its find from time to time. But herds of (living) cows kept coming through the site, and though the badger checked on its cache several times, it never re-entered the burrow after March 6.

It turns out that this badger was not alone in taking advantage of the research project for a huge, free meal. Simultaneously at one of the other carcass sites about three kilometers away, another badger attempted to bury a calf that had been staked out there. It only got the job partway done, though, as the anchoring stake prevented the badger from finishing a full burial. Instead, the badger dug itself a hole and spent several weeks there, periodically feeding on its find.

This is the first time scientists have documented American badgers burying a carcass so much bigger than themselves (the calves were three to four times the weight of the badgers), the team reports March 31 in Western North American Naturalist.

“All scavengers play an important ecological role — helping to recycle nutrients and to remove carrion and disease vectors from the ecosystem,” Frehner says. “The fact that American badgers could bury carcasses of this size indicates that they could potentially bury the majority of the carrion that they would come into contact with in the wild. If they exhibit this behavior across their range, the American badger could be accounting for a significant amount of the scavenging and decomposition process which occurs throughout a large area in western North America.”

And that burial may have a benefit for ranchers, the researchers note: If badgers bury calves that have died of disease, that may reduce the likelihood that a disease will spread. It’s too soon to say whether that happens, but study co-author Evan Buechley notes, “that merits further study.”