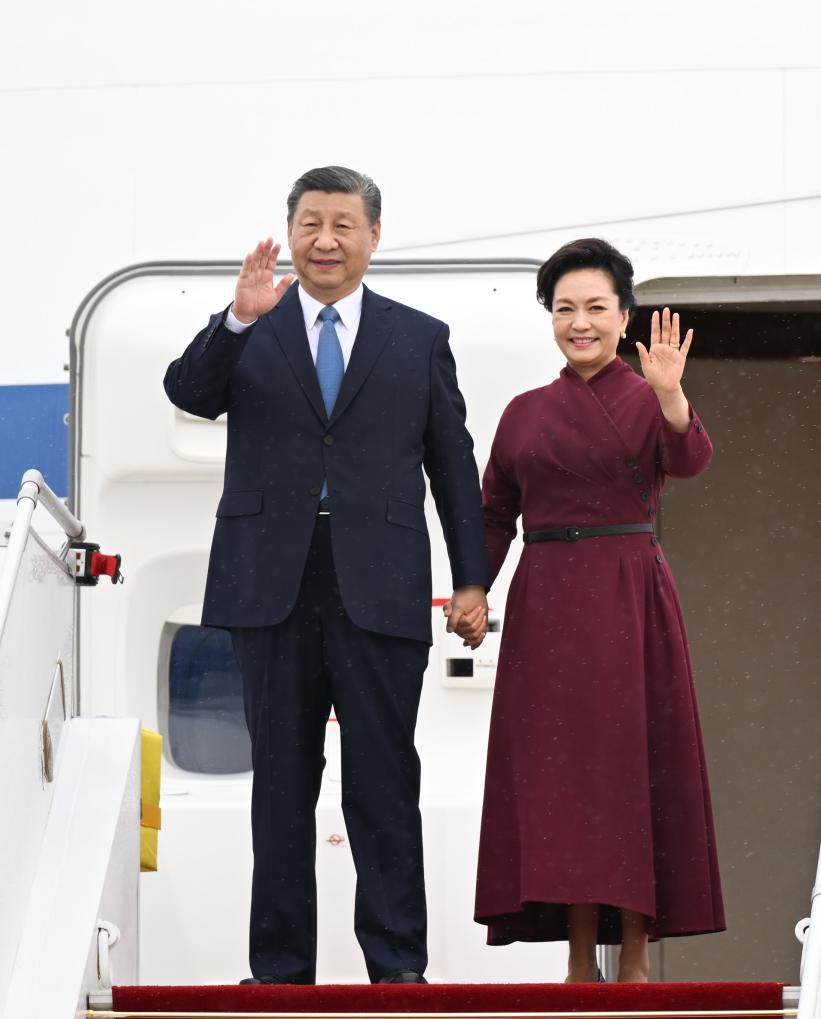

Xi starts state visit to France, commends bilateral relations

Chinese President Xi Jinping arrived in Paris on Sunday afternoon local time, the first stop of his visit to three European countries. In a written speech on Sunday upon his arrival for a state visit to France, Xi said over the past 60 years, China-France relations have long been at the forefront of China's ties with major Western countries, setting a good example for the international community of peaceful coexistence and win-win cooperation between countries with different systems.

The development of China-France relations has not only brought benefits to the two peoples, but also injected stability and positive energy into the turbulent world, Xi said in the written speech.

Xi's visit to France comes at a time when this year marks the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and France. Analysts believe the visit will boost leadership exchanges, strengthen political trust and offer an opportunity for China-Europe relations to move forward in a stable and steady manner.

"President Xi will have comprehensive and in-depth strategic communication with French President Emmanuel Macron on China-France and China-Europe relations, encourage France to uphold strategic autonomy and openness in cooperation, so as to drive Europe to form a more independent, objective, and friendly understanding of China and resist negative trends such as 'de-risking' and 'reduced dependence' on China," Chinese ambassador to France Lu Shaye told a press briefing on April 29 after China made the announcement of the visit.

Pierre Picquart, an expert in geopolitics and human geography from the University of Paris-VIII, told the Global Times that Xi's visit is significant on three levels.

"On the economic front, this trip could pave the way for reaching trade agreements and promoting mutually beneficial investments in key sectors such as technology, innovation, energy and infrastructure. Diplomatically, this visit provides an ideal platform to strengthen coordination and collaboration between China and France on major global challenges such as climate change, international security and public health. On cultural and educational level, this trip could open up new opportunities for cooperation in the fields of education, research and culture, thereby strengthening exchanges between our peoples and deepening their mutual understanding," Picquart said.

Commemorative events

The national flags of China and France have been raised at one end of the Avenue des Champs-Élysées as well as on the street in front of Les Invalides.

On Sunday afternoon, near the Arc de Triomphe in the center of Paris, many local Chinese residents and Chinese students waved the national flags of China and France to welcome President Xi. The red banners that read "Long live China-France friendship" and "Wish President Xi a successful visit to France" were very eye-catching. Some also staged dragon and lion dances in show of a joyful atmosphere.

Prior to Xi's visit, several events had been held in preparation for Xi's visit as well as to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and France.

The Second Forum on China-France Global Governance was jointly held on Thursday by the Academy of Contemporary China and World Studies and China-Europe-America Global Initiative. Themed "Deepening global governance reforms, jointly building the future of multilateralism," the forum invited more than 100 Chinese and French scholars to share their views on the role of China and France in building a more just world.

Pascal Boniface, director of the Paris-based Institute for International and Strategic Affairs, told the Global Times at the event, hoping that Xi's visit can address such issues as preserving multilateralism, as "we are at a time when we have the war between Russia and Ukraine, the war in Gaza and a lot of turmoil in the Middle East."

On Friday, a symposium themed "Exchanges and Mutual Learning between the Chinese and French Civilizations: Review and Outlook," was jointly organized by the Beijing-based Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) and the Paris-based National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations. Around 100 researchers from the two countries held discussions on the practice of cross-cultural exchanges between China and France and scientific and technological innovation and the future of civilization.

Antoine Broussy, director of the Charles de Gaulle Foundation, told the Global Times that many commemorations are taking place in Paris.

Seeking common interests

Sixty years ago, France became the first Western country to establish diplomatic relations with China. Broussy believes it was "the result of a rational analysis of the geopolitical situation at the time." Then French president, General Charles De Gaulle who made the decision, was a strong advocate for "strategic autonomy" of France. Nowadays, France's call for "strategic autonomy" of both France and Europe has been repeatedly coming from French President Macron.

When co-chairing the 25th China-France Strategic Dialogue in Paris in February with French President's Diplomatic Counselor Emmanuel Bonne, Wang Yi, Member of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and Director of the Office of the Central Commission for Foreign Affairs, said China supports Europe in strengthening its strategic autonomy and holding its future in its own hands.

Nonetheless, the "strategic autonomy" of Europe has rarely been endorsed by Washington. During Macron's visit to China last year when he warned Europe against being drawn into a conflict between the US and China over Taiwan, US magazine Foreign Policy called strategic autonomy "a French pipe dream."

He Zhigao, a research fellow with the Institute of European Studies of CASS, told the Global Times that the US wants to hold tight control of Europe to tie it to the Western camp led by Washington.

"If Europe views China from a global perspective that could benefit the world, then China is an opportunity. But if it stands by US' side, then China must be a challenge," said He, adding that China's engagement with Europe is for the common development.

As of 2021, China has been the largest Asian country in terms of investment and job creation in France for three consecutive years, according to a report by Business France. China-France exchanges in core sectors such as aerospace, nuclear energy and trade have already realized fruitful achievements, and the development of emerging fields such as new energy and the digital economy are likely to become new growth engines.

Sun Keqin, a research fellow at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, told the Global Times that France also views China as an important external force to achieve strategic autonomy, as France has another ambition of strengthening France's leadership of Europe.

Xin Hua, director and chair professor of the Center for European Union Studies, Shanghai International Studies University, believes China-France relations serve as the ballast stone of China-Europe relations.

"France is one of the most important core members of the EU and its strategic orientations play a decisive role in the EU's integration process and the strategic and security pattern of the European continent. As long as China and France maintain positive interaction, China-Europe relations will stay stable," said Xin.