Live long and prosper

In Science News’ special report on aging (SN: 7/23/16, p. 16), writers Laura Sanders, Tina Hesman Saey and Susan Milius explored the latest research — from the evolution of aging in the animal kingdom to scientists’ quest to delay the process in humans’ bodies and minds.

“I would very much like to know how research into aging may benefit people who are middle-aged or elderly now?” asked leftysrule200 in a Reddit Ask Me Anything about the special report. “Is there any research that can result in treatments in the very near future, or are the real-world applications only going to be visible in the distant future?”

Middle-aged and elderly people will be the first to benefit from aging research, Saey says. “A clinical trial using the diabetes drug metformin as an antiaging therapy will begin soon. That drug will be tested on healthy people aged 60 and older,” she says.

Sanders cautions that most antiaging treatments are still a long way off. But various studies in rodents and humans provide potential clues to aging’s secrets. Blood from young rats, for instance, has been shown to rejuvenate the bodies and brains of old rats. Based on those findings, a clinical study in humans is now under way that is looking at the effects of plasma from young donors on the brains of people with Alzheimer’s. “If scientists could pinpoint the compounds that give young blood its power, then they could presumably develop drugs that mimic that process,” Sanders says.

In the meantime, people may be able to slow the effects of aging by leading a healthy lifestyle. Sanders points to a long-term study of middle-aged women in Australia. Women who were more physically active had sharper memories 20 years later, the researchers found. Until proven antiaging treatments are available, “it seems that keeping the body physically active and strong is one of the best ways to keep your brain sharp as you age,” she says.

Dino spills its guts

Tiny tracks discovered in the blackened stomach contents of a 77-million-year-old duck-billed dinosaur fossil suggest gut parasites infected dinosaurs, Meghan Rosen reported in “Parasites wormed way into dino’s gut” (SN: 7/23/16, p. 14).

Online reader Jim Stangle Dvm thought the worms may not have been parasites at all. “It is more likely that the tunnels were formed by a scavenger worm [after the dino had died]. Still I think the findings are way cool!” he wrote.

It’s hard to say definitively whether the burrows were made by parasites or not, says paleontologist Justin Tweet. Scavenger worms could have tunneled through the gut after the dino’s death, but his team found only one type of worm burrow “which suggests that either only one kind of scavenger had access to the carcass,” or “that these burrows were an inside job,” Tweet says.

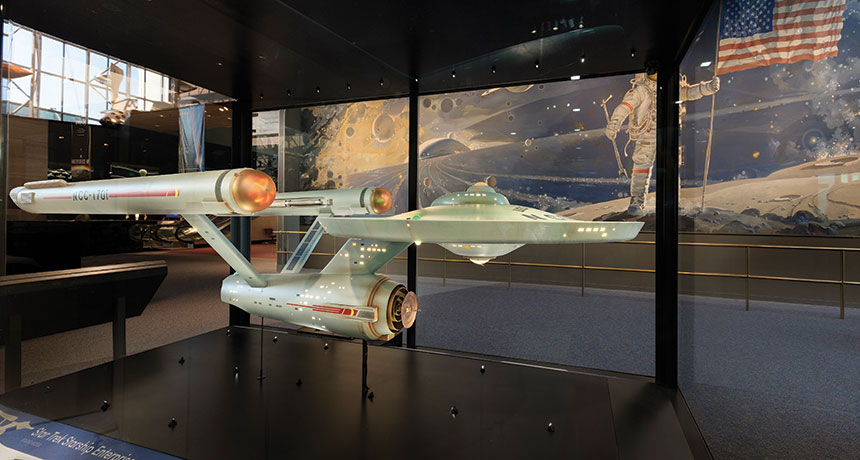

That’s no moon!

A recently discovered asteroid appears to orbit Earth, but that’s just an illusion. The asteroid orbits the sun, but its constant proximity to Earth makes it the planet’s only known quasisatellite, Christopher Crockett reported in “Say What? Quasisatellite” (SN: 7/23/16, p. 5).

Reader Mike Lieber wondered if the moon could also be a quasisatellite. “The gravitational attraction of the sun on the moon is twice that of the Earth,” he wrote. “It seems that the apparent looping of the moon around the Earth is also illusory.”

The moon is a true satellite, Crockett says. If the sun were to disappear, the moon would continue orbiting Earth. “The moon is within Earth’s ‘Hill sphere,’ the volume of space in which Earth’s gravity is the dominant influence,” he says. “The strength of the gravitational force isn’t as important as by how much it changes from one place to another.” Given the moon’s proximity to our planet, Earth prevails. “The moon orbits Earth and the Earth-moon system orbits the sun,” he says.