Need a fall read? ‘The Song of the Cell’ offers tales from biology and history

In the summer of 1960, doctors extracted “crimson sludge” from 6-year-old Barbara Lowry’s bones and gave it to her twin.

That surgery, one of the first successful bone marrow transplants, belied the difficulty of the procedure. In the early years of transplantation, scores of patients died as doctors struggled to figure out how to use one person’s cells to treat another. “Cell therapy for blood diseases had a terrifying birth,” Siddhartha Mukherjee writes in his new book, The Song of the Cell.

The transplant story is one of many Mukherjee uses to put human faces and experiences at the heart of medical progress. But what radiates off the pages is the author himself. An oncologist, researcher and Pulitzer Prize–winning author, Mukherjee’s curiosity and wisdom add pep to what, in less dexterous hands, might be dry material. He finds wonder in every facet of cell biology, inspiration in the people working in this field and “spine-tingling awe” in their discoveries.

It’s no surprise that Mukherjee is so seduced by science. This is a man who built a microscope from scratch during the pandemic and has spent years probing biology and its history with luminaries in the field. The Song of the Cell lets readers eavesdrop on these conversations, which can be intimate and enlightening.

On a car ride across the Netherlands, Mukherjee chats with geneticist Paul Nurse, who tells him about the cell division work that ultimately netted Nurse a Nobel Prize (SN: 3/27/21, p. 28). On a walk at Rockefeller University in New York

City, Mukherjee discusses his depression with another Nobel Prize–winning researcher, neuroscientist Paul Greengard. Mukherjee’s vivid imagery lends heft to his feelings. He tells Greengard about experiencing a “soupy fog of grief” after his father’s death and describes “drowning in a tide of sadness.”

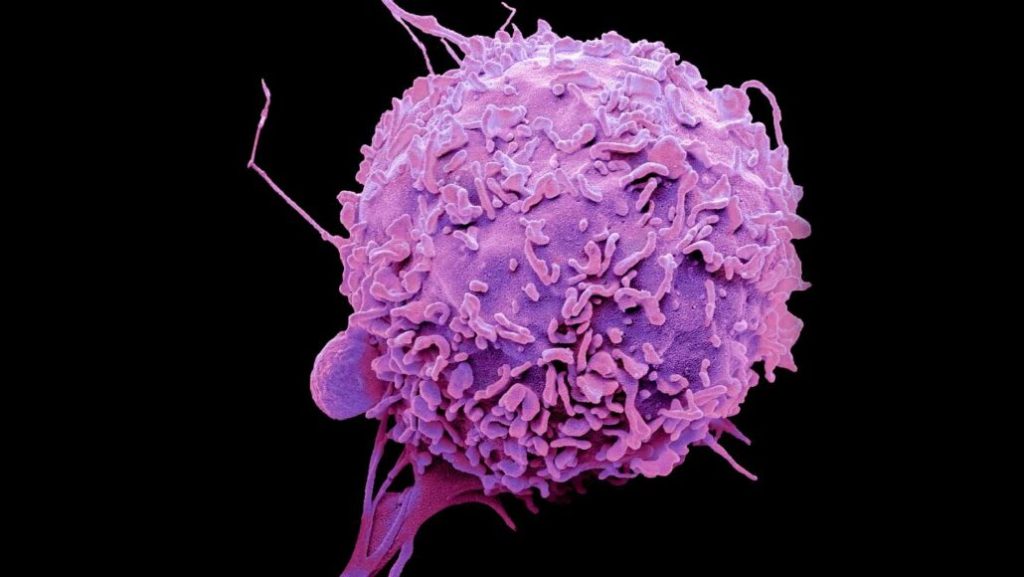

In these memories, which Mukherjee uses to segue into the science of depression, and elsewhere in the book, hints of poetry shimmer among the prose. A cell observed under a microscope is “refulgent, glimmering, alive.” A white blood cell’s slow creep is like the “ectoplasmic movement of an alien.” Mukherjee weaves his experiences into the story of cell biology, guiding readers through the lives and discoveries of key figures in the field. We meet the “father of microbiology,” Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, a 17th century cloth merchant who ground globules of Venetian glass into microscope lenses and spied a “marvelous cosmos of a living world” within a raindrop. Mukherjee also teleports us to the present to introduce He Jiankui, the disgraced biophysicist behind the world’s first gene-edited babies (SN: 12/22/18 & 1/5/19, p. 20). Along the way, we also meet Frances Kelsey, the Food and Drug Administration medical officer who refused to approve thalidomide, a drug now known to cause birth defects, for use in the United States, and Lynn Margulis, the evolutionary biologist who argued that mitochondria and other organelles were once free-living bacteria (SN: 8/8/15, p. 22).

Mukherjee traverses a vast landscape of cell biology, and he’s not afraid to pull over and go exploring in the weeds. He describes in detail the flux of ions in nerve cells and introduces a considerable cast of immune system characters. For an even deeper dive, readers can check the footnotes; they are abundant.

What stands out most, though, are Mukherjee’s stories about people: scientists, doctors, patients and himself. As a researcher and a physician, he steps deftly between the scientific and clinical worlds, and, like the microscope he assembled, offers a glimpse into a universe we might not otherwise see.