Six months in space leads to a decade’s worth of long-term bone loss

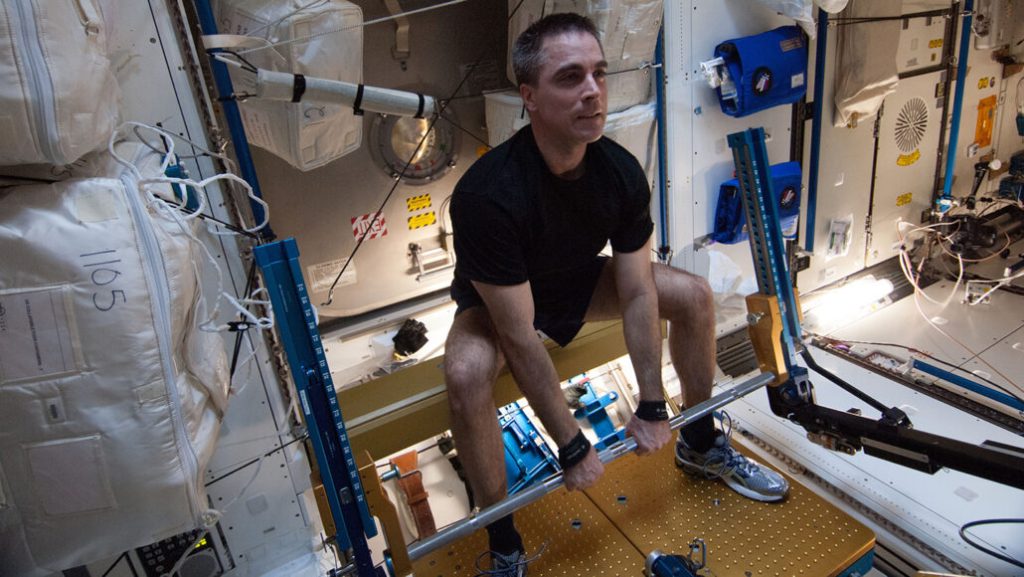

You might want to bring your dumbbells on that next spaceflight.

During space missions lasting six months or longer, astronauts can experience bone loss equivalent to two decades of aging. A year of recovery in Earth’s gravity rebuilds about half of that lost bone strength, researchers report June 30 in Scientific Reports.

Bones “are a living organ,” says Leigh Gabel, an exercise scientist at the University of Calgary in Canada. “They’re alive and active, and they’re constantly remodeling.” But without gravity, bones lose strength.

Gabel and her colleagues tracked 17 astronauts, 14 men and three women with the average age of 47, who spent from four to seven months in space. The team used high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography, or HR-pQCT, which can measure 3-D bone microarchitecture on scales of 61 microns, finer than the thickness of human hair, to image the bone structure of the tibia in the lower leg and the radius in the lower arm. The team took these images at four points in time — before spaceflight, when the astronauts returned from space, and then six months and one year later — and used them to calculate bone strength and density.

Astronauts in space for less than six months were able to regain their preflight bone strength after a year back in Earth’s gravity. But those in space longer had permanent bone loss in their shinbones, or tibias, equivalent to a decade of aging. Their lower-arm bones, or radii, showed almost no loss, likely because these aren’t weight-bearing bones, says Gabel.

Increasing weight lifting exercises in space could help alleviate bone loss, says Steven Boyd, also a Calgary exercise scientist. “A whole bunch of struts and beams all held together give your bone its overall strength,” says Boyd. “Those struts or beams are what we lose in spaceflight.” Once these microscopic tissues called trabeculae are gone, you can’t rebuild them, but you can strengthen the remaining ones, he says. The researchers found the remaining bone thickened upon return to Earth’s gravity.

“With longer spaceflight, we can expect bigger bone loss and probably a bigger problem with recovery,” says physiologist Laurence Vico of the University of Saint-Étienne in France, who was not part of the study. That’s especially concerning given that a crewed future mission to, say, Mars would last at least two years (SN: 7/15/20). She adds that space agencies should also consider other bone health measures, such as nutrition, to reduce bone absorption and increase bone formation (SN: 3/8/05). “It’s probably a cocktail of countermeasure that we will have to find,” Vico says.

Gabel, Boyd and their colleagues hope to gain insight on how spending more than seven months in space affects bones. They are part of a planned NASA project to study the effects of a year in space on more than a dozen body systems. “We really hope that people hit a plateau, that they stop losing bone after a while,” says Boyd.